Nuclear Monitor #924

Oda Becker, Independent expert (Germany),

Gabriele Mraz, Austrian Institute of Ecology

Introduction

The global nuclear reactor fleet is increasingly ageing. Most reactors were designed for a lifetime of 30-40 years. When they are operated beyond their design life, it is called lifetime extension, or long-term operation. The second term is used by pro-nuclear organizations, while critical experts prefer the term “lifetime extension” to make visible that the original design life has been reached. Nevertheless, the term “lifetime extension” does not have a legal basis. This has lead to an unclear situation concerning participation of the public.

In some countries, nuclear power plants are granted unlimited operating licenses, other countries issue licenses that are limited in time, and in some countries the operating life of a nuclear power plant is regulated by law. Regular periodic safety reviews (PSR), which must be carried out every 10 years, should ensure safe operation in all cases.

The World Nuclear Industry Status Report gives a yearly up-to-date overview of the age of the global reactor fleets. In January 2025, the mean age of the global reactor fleet was 32.1 years[1]. In the European Union, the mean age is even higher, in September 2024 it was 38.4 years[2]. The world’s oldest reactor is still operating in the middle of Europe – Beznau in Switzerland started in 1969 and therefore is now 56 years in operation.

One of the most recent lifetime extension project is NPP Borssele in the Netherlands. Borssele consists of one reactor with 485 MegaWatt(electric). It is in operation since 1973. According to Art. 15a of the Dutch Nuclear Energy Act, Borssele may continue to produce energy only until the end of 2033, which corresponds to a service life of 60 years. The operating life is now to be extended due to a political decision from 2021. This requires an amendment of the Nuclear Energy Act. An Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is being carried out for this amendment; a second EIA phase is also planned.

In this article we will discuss possibilities for public participation in life-time extension procedures and highlight the risks of lifetime extension of an old NPP in general and for Borssele in particular.

Participation in lifetime extension procedures

The majority of lifetime extensions in the EU and neighboring third countries have so far taken place without the population having a say. This contradicts the intention of important international conventions (ESPOO and Aarhus[3]) and the EU directives on environmental impact assessments (EIA) and strategic environmental assessments (SEA).

The above mentioned unclear legal situation on what is a lifetime extension and what is not was discussed in detail in the Espoo Convention Implementation Committee already more than 10 years ago. In 2014, the Implementation Committee decided that the lifetime extension of the concrete case of the Ukrainian NPPs Rivne-1&2 would have needed an EIA. Rivne-1&2 started operation in 1980/81. In 2010, their lifetime was extended by 20 years without making an EIA, which was challenged at the Espoo Convention Implementation Committee by the Ukrainian NGO Ecoclub. Both nuclear-free countries such as Austria and major international NGOs assumed after the Rivne decision in 2014 that lifetime extensions for all NPPs would from now on fall within the scope of the ESPOO Convention and would need to be subjected to a transboundary EIA. Since 2020 there is the “Guidance on the applicability of the Convention to the lifetime extension of nuclear power plants”[4] in force, but still many states take a different view and license their lifetime extensions without an EIA.

Why is it so important that an EIA takes place? In many countries, an EIA is the only legally secured participation procedure that is open for the general public, especially for NPPs outside the own country. Some countries only offer participation for the local or regional population around the NPP site, some countries conduct voluntary procedures.

Moreover, in an EIA all environmental impacts of an activity need to be assessed, this includes not only noise and dust during construction but also dangers for habitats of plants and animals, nuclear waste management, radioactive emissions during normal operation and – most important in a transboundary context – consequences of severe accidents.

Even before their lifetime extension, old European NPPs have not been subjected to an EIA at all because the first EU EIA law only came in force in 1985 (only valid for EU member states), and the ESPOO Convention in 1997 (only valid for signatory countries). A comprehensive assessment of the environmental impacts of these old NPP is therefore missing at all; a first EIA during lifetime extension is necessary to fill this gap.

NGOs complain about missing participation (esp. EIA) in the lifetime extension procedures of old NPP in different ways, by going to Court, by making a complaint at the Espoo Implementation Committee or at the Aarhus Convention Compliance Committee (ACCC).

This was also the case when the lifetime of the NPP Borssele in the Netherlands should be extended. Borssele was designed with a lifetime of 40 years. It started operation in 1973. After 40 years, in 2013, in the Nuclear Energy Act Article 15a was changed allowing the lifetime to be extended until 2033. This extension did not include an EIA. Greenpeace Netherlands made a complaint at the ACCC resulting in a decision in 2018. The ACCC “considers it inconceivable that the operation of a nuclear power plant could be extended from 40 years to 60 years without the potential for significant environmental effects. The Committee accordingly concludes that it was “appropriate”, and thus required, to apply the provisions of article 6, paragraphs 2-9, to the 2013 decision amending the licence for the Borssele NPP to extend its design lifetime until 2033.”[5] Article 6 of the Aarhus Convention regulates public participation in decisions on specific activities. The Aarhus Convention does not require an EIA as such, but comprehensive, comparable public participation.

In 2021, a decision of the ACCC and the Meeting of the Parties of the Aarhus Convention was taken that the public did not have sufficient participation possibilities when Art 15a was included in the Nuclear Energy Law in 2010.

In 2024, the long overdue EIA started, two phases are foreseen The first phase deals with the environmental impacts of changing Article15 of the Nuclear Energy Act. This EIA phase 1 provides the scope for environmental impacts that need to be discussed in detail in EIA phase 2. For the first EIA phase, an environmental impact report.

Technical risks of lifetime extension

As in any industrial plant, the quality of the materials used in a nuclear power plant decreases over time due to aging. In addition, the safety design of the nuclear power plant becomes outdated in relation to current safety requirements. It is not possible to replace all safety-relevant components affected by aging, nor is it possible to eliminate all design weaknesses through modernization measures.

The Borssele NPP, one of the oldest operating NPP in the world, is a 2-loop Pressurized Water Reactors (PWR) constructed by the German company Siemens/KWU. Four different constructions lines (CL) were developed and operated. The Borssele NPP belongs to the oldest CL 1, both other reactors of CL 1 have been already shut down permanently in 2003 (Stade, Germany) and 2005 (Obrigheim, Gemany), respectively. Besides three younger reactors in Spain, Switzerland and Brasilia, all KWU reactors were shut down permanently.

The original safety report of the Borssele NPP covered a 40-year operational lifetime, equating to the closure in 2013. However, in 2006, a political agreement (“Borssele Covenant”) allowed the operation to 2033 under certain conditions. One requirement is that the Borssele NPP belongs to the top 25% in safety of reactors in the EU, Canada and the USA. To assess whether Borssele NPP meets this requirement, the Borssele Benchmark Committee has been established. In its third report, the committee has selected important safety-related points of the design for comparative evaluation.[6] However, other important design features are missing, such as the thickness of the reactor building.

Apart from the fact that the Committee’s assessment is not very credible, especially in view of the results of the safety review of the German Technical Support Organisation (TSO) GRS (Gesellschaft für Anlagen- und Reaktorsicherheit, engl. Plant and Reactor Safety Company)[7], a comparison with the safety level of new nuclear power plants should be made to assess the safety level of the Borssele NPP.

In 2008, the German TSO GRS developed a procedure for comparing the safety of German NPPs of the different ages. The comparison showed that the NPP Neckarwestheim-1 (GKN-1), commissioned in 1976 (KWU CL 2) had a safety disadvantage in 17 of 23 assessment objects compared to GKN-2 (1989, KWU CL 4). Weaknesses were found at all levels of the defense-in-depth concept, i.e. the safety concept that is intended to prevent accidents and prevent their potential effects (conceptual outdated design).

The comparison also revealed that the average annual event rates at GKN-1 are significantly higher in the area of events with ageing relevance; actually, the number is four times higher (technical ageing). The ageing management programme of the Borssele NPP has weaknesses as the results of the current IAEA OSART mission revealed. The results of the OSART mission contradict the statements of the EIA REPORT (2024) that the ageing management effectively prevents physical ageing as well as technological ageing (obsolescence).[8]

Accident analysis

The provided EIA documents give some information about Design Basis Accidents (DBA). The information about Beyond Design Basis Accidents (BDBA), however, is very limited. Neither the accident scenarios nor the possible source terms (amount of release of radioactive substances in case of a severe accident) are provided. According to the EIA REPORT (2024), the calculated core damage frequency (CDF) has decreased due to backfitting. However, information on frequencies for large releases (LRF) is not provided. Even though the calculated probability of severe accidents with a large release is very low, the consequences caused by these accidents are potentially enormous.

Core-melt accidents can cause a failure of the containment. These scenarios are associated with large releases. In 2017, an in-vessel molten core retention by creating a cooling opportunity of the outside of the reactor vessel has been implemented. This could be an important safety improvement. But still other scenarios are possible. To assess the consequences of BDBAs, it is necessary to analyze a range of severe accidents, including those involving containment failure and containment bypass. Such severe accidents are possible for the Borssele NPP.

According to ANVS (2019), the probabilistic safety analyses (PSA) Level 2 demonstrated that Steam Generator Tube Rupture (SGTR) events with a dry secondary side of the steam generator could cause the largest source terms (up to 50% Cesium and Iodine inventory of the core).[9] By a backfitting measure, the possible source term could only be reduced but will still remain high. Furthermore, the function of retrofitting in an accident situation is not guaranteed.

Terror attacks and acts of sabotage

Terrorist attacks and acts of sabotage can have significant impacts on nuclear facilities and cause severe accidents – also on the Borssele NPP. Nevertheless, they are not mentioned in the provided EIA documents. In comparable EIA Reports such events were addressed to some extent. Although precautions against sabotage and terror attacks cannot be discussed in detail for reasons of confidentiality, the necessary legal requirements should be set out in the EIA documents.

This topic is in particular important because the reactor building of the Borssele NPP is vulnerable against airplane crashes. The reactor building should protect the plant against attacks from outside. This needs a wall thickness of the reactor building of almost 2 m. However, the wall thickness at the Borssele NPP is only about 0.6 m to 1.0 m.

Furthermore, a recent assessment of nuclear security in the Netherlands points to shortcomings compared to necessary requirements for nuclear security. The US Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI) assessed the measures taken by different countries to protect against terrorist attacks and sabotage in their nuclear facilities in the so-called Nuclear Security Index 2023. In the NTI Index, 100 corresponds to the highest possible score and thus to the fulfillment of the current security requirements. Low scores for “Insider Threat Prevention” (73) and “Security Culture” (50) indicate deficiencies in these issues.[10]

Military action against nuclear facilities is another danger that needs special attention in the current global situation. Furthermore, the increasing availability and performance of drones is raising the potential threat to nuclear facilities.

Consequences of a severe accident in Borssele

In case of a severe accident in Borssele, almost all parts of Europe could be affected, but with different probability. The project flexRISK[11] identified source terms for severe accidents, for Borssele a possible source term of 31.87 Petabecquerel Cs-137. This source term was calculated with respect to the behavior of the plant in case of a severe accident and the possible release.

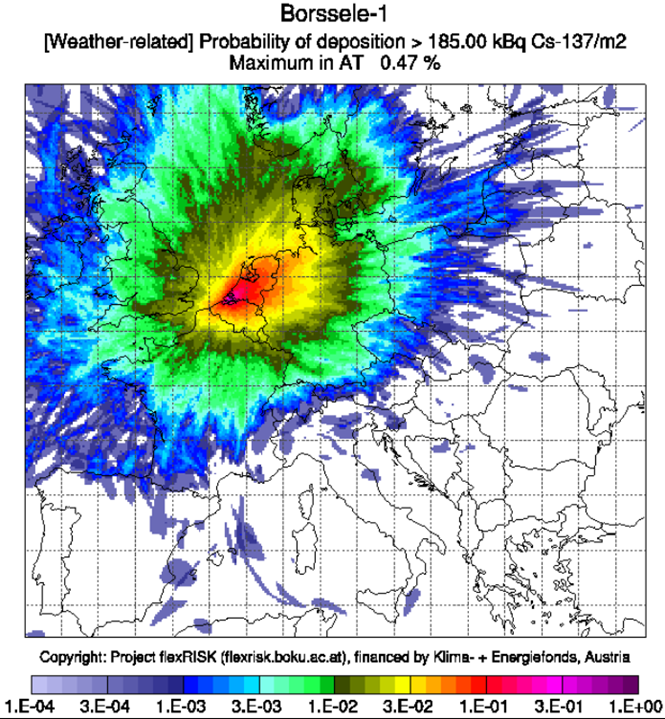

Calculations of the flexRISK project can be used for the estimation of possible impacts of transboundary emission of Borssele. For about 2,800 meteorological situations the large-scale dispersion of radionuclides in the atmosphere was simulated. For example, flexRISK determined the weather-related probability for a contamination of European territory with more than 185 Kilobecquerel Cs-137/m2 by a severe accident in Borssele. 185 kBq Cs-137/m2 was the Belarussian threshold for zones with the right to resettlement after the accident of Chernobyl.

Results are shown in the following figure. The scale starts at 1E+00 = 1 = 100% which means that in every of the 2,800 weather situations the dark violet area will be contaminated with more than 185 kBq Cs-137/m2 in case of such a severe accident (this is the area in the direct vicinity of the NPP). Larger parts of western Europe are in the red, orange and yellow areas, meaning that they have a weather-related probability of a few up to about 10% to be contaminated this high. Austria, which is in a larger distance, has a probability of 0.47% to be affected.

Conclusions

Lifetime extension of old nuclear power plants as the Borssele NPP increases the risk of severe accidents in Europe. The ageing of nuclear power plants possess a significantly risk of severe accidents and radioactive releases. This significantly increased risk is further significantly increased by the continued operation of old plants as a result of lifetime extensions. Furthermore, essential safety principles (such as protection against external events) were not applied or only to a limited extent at the time of construction. From today’s perspective, old nuclear power plants such as the Borssele nuclear power plant have numerous design weaknesses. With the increasing age of the plant, these conceptual deviations from the safety level required today for new plants are becoming ever greater.

In addition, new threat scenarios have emerged. Terrorist attacks and extreme natural events, e.g. as a consequence of climate change, can no longer be neglected as real dangers. In principle, backfitting measures are limited. Significant design weaknesses of old nuclear power plants remain.

The risks of the Borssele nuclear power plant must be known to political decision-makers and the public in order to be able to assess their safety. Therefore, it is of uttermost importance that the public is involved in decision-making on lifetime extension of old NPP, it the resulting risk is acceptable for society or not.

Further reading:

INRAG: “Risks of lifetime extension of old nuclear power plants” (2021): https://www.inrag.org/risks-of-lifetime-extension-of-old-nuclear-power-plants-download

Oda Becker, Kurt Decker, Gabriele Mraz (2024): NPP Borssele LTE Phase 1. Environmental Impact Assessment. Expert statement. https://www.umweltbundesamt.at/fileadmin/site/publikationen/rep0931.pdf

[1] WNISR 2024, https://www.worldnuclearreport.org/

[2] https://www.worldnuclearreport.org/European-Union

[3] The Espoo Convention is the legal framework for transboundary Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA); she entered into force 1997. The Aarhus Convention regulates access to information, public participation and access to justice in environmental matters; she entered into force in 2001. Both Conventions includes NPP in their scope.

[4] https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2021-07/2106311_E_WEB-Light.pdf

[5] https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/pp/compliance/CC-63/ece.mp.pp.c.1.2019.3.en.pdf, point 71

[6] Borssele Benchmark Committee (2023): Safety benchmark of Borssele, Nuclear Power Station; Report of the Borssele Benchmark Committee; November 2023.

[7] https://www.grs.de/en

[8] Environmental Impact Assessment. Amendment of the Nuclear Energy Act. Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy. 14. June 2024.

[9] Authority for Nuclear Safety and Radiation Protection (2019a): Convention on Nuclear Safety (CNS): National Report of the Kingdom of the Netherlands for the for the Eighth Review Meeting, 2019

[10] NTI Nuclear Security Index 2023: The NTI Index for the Netherlands. https://www.ntiindex.org/

[11] http://flexrisk.boku.ac.at/en/projekt.html